Home > Learn about US 12 Heritage Route > Heritage Trail Story

Heritage Trail Story

In 1825, the United States government appropriated $3,000 for a federal highway, the second in the nation, which was laid out along an ancient Indian trail. Maintained almost continually by federal, state, and local governments, the highway has been used constantly through the present. Today, the US-12 Heritage Trail traverses the State of Michigan retaining an invaluable legacy of structures, artifacts, and landscapes. These structures represent an environment that reflects the needs of both southern Michigan's travelers and settlers.

The US-12 corridor and the areas adjacent have been used since prehistoric times. Near Saline and parallel to the highway, paleontologists from the University of Michigan have excavated portions of the longest mastodon trailway ever found, suggesting that game animals were using the corridor over 10,000 years ago. The indigenous people of Michigan who hunted the animals followed, establishing their migratory routes. Although the history of these peoples is not thoroughly documented, evidence of their use of the corridor remains. Burial and encampment sites have been identified along the highway. In Sturgis, a marker identifies a bent tree reported to have been a trail marker used by the native people. When the Europeans first entered Michigan in the seventeenth century, the route was already a well-established pathway through the wilderness. It roughly followed from Lake Erie to Lake Michigan, a geographical line where the abundant forests of the north gave way to the more open grasslands of the south. During the early history of European dominance the trail was used by both native people and the French in the lucrative fur trading profession. After the British gained control of the region, the indigenous people continued to use the trail as they seasonally traveled to receive their yearly stipend from the British at Fort Malden.

Early Developmental Stages

Through the early part of the American era, such a travel pattern continued, but when the Erie Canal opened in 1825, settlers were able to reach the Michigan Territory by water, turning the nation's westward push to the north. In this movement, the US-12 Heritage Trail played a key role, as settlers left their boats in Detroit to travel overland to Chicago and points in between. The great flood of settlers soon created such a demand for land that the two government land offices located in Detroit and Monroe became insufficient. The White Pigeon Land office opened in 1831 and remained in operation for a little less than three years. During that short period of time the office processed patents on almost all of the territory in southern Michigan west of the meridian line, including the downtown sections of several of Michigan's large cities: Grand Rapids, Kalamazoo, and Battle Creek. This building now operates as a local museum and is still extant along the highway.

Inns and Taverns

|

| The building survives in Saline but has lost its character |

|

The best preserved of these inns is the Walker Tavern at the junction of the Chicago Road (currently US-12) and the La Plaisance Bay Pike (currently M-50) which ran from Monroe. The tavern, built in 1832, was purchased in the late 1830s by Sylvester Walker and offered little in the way of modern comforts. There were few sleeping rooms and travelers often shared beds or slept on the floor. The tavern also served as a community center,and church services were held in the bar on Sundays. When Sylvester Walker wanted to expand his business he built a second tavern across the highway. The new brick building offered private rooms, a dining hall, and on the third story a dance hall. Inns and taverns are among the most prominent early artifacts along the route. The Davenport House on Evans Lake began serving stage passengers in 1839, replacing an earlier log structure. In Clinton a state historical marker indicates the original site of the Eagle Tavern/Clinton Inn. The tavern was moved to Greenfield Village (Detroit) in 1927.

Agricultural Influences

|

During the early development along the highway, a settlement pattern emerged of small towns surrounded by fields and open land. The historic rhythm of this pattern remains very much in evidence today. Spaced at about fifteen mile intervals, small towns like Saline, Clinton, Jonesville, Allen, Quincy, Bronson, Sturgis, White Pigeon, and Niles lined up facing the highway that was responsible for their existence.

|

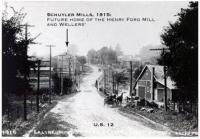

Towns grew as service areas to agricultural hinterlands and were usually located at the junction of the travel route or along a river where water power was plentiful for operating the saw and grist mills needed by the settlers. Several mills remain at these historic junctions along the route including the Atlas Mill in Clinton and the Pears Mill in Buchanan. The most prominent is the Schuyler Mill built in 1843 on the fall of the Saline River, in the then Village of Barnegat (now known as Saline). In a later period of the road's history, Henry Ford purchased the mill in 1935. Along with a dam to provide water power and several new buildings, Ford made major renovations to the mill. The mill was the centerpiece for his village industry located in Saline. The buildings and structures along both sides of the highway are listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Influences of the Railroad

|

| Saline Depot |

Innovations in travel changed the corridor in the post Civil-War days. The railroad soon replaced earlier forms of transportation. It did not, however, diminish the use of the transportation corridor. Railroad companies recognized the geographical suitability of the corridor and communities located along the old stage route vied heartily for inclusion along the new right-of-way.

Early Industrial Influences

Industries sprang up near the source of the raw material they utilized. What were originally small and medium-sized farming villages subsequently became manufacturing centers sending their products across the nation. For example, sheep raisers from the English town of Manchester settled just north of the trail, making Washtenaw County one of the leading wool producers in the nation. In the heart of the sheep raising area, Clinton was a thriving trade center, the largest village west of Detroit on the trail. Two rail lines crossed there making Clinton an excellent site for manufacturing. In 1866, a small group of businessmen formed the Clinton Woolen Mill. Using local Manchester wool, the mill manufactured clothing for soldiers in the two World Wars and the Spanish-American War, cloth for fire and police uniforms, and eventually material for automobile upholstery. The mill burned twice, once shortly after it opened and again in 1886 as a result of an explosion. Both times it was rebuilt within months. The mill closed in 1957, but the jobs and affluence it helped to produce left a legacy of beautiful old housing stock and once prosperous commercial buildings.

Federal Highway System Designation

|

Just as the railroad began to replace the horse and wagon, so a new means of transportation replaced the railroad; the automobile and the motor truck. As they rose to dominance, the face of the US-12 Heritage Trail changed once again, the focus returning to the road. Developing as the center of the automobile industry, Michigan became a leader in the good roads movement. Henry B. Joy, the president of the Packard Motor Car Company led the promotion of the first transcontinental highway. He petitioned Congress to develop a national plan to develop and improve the highway system. In response, Congress passed the Federal Aid Road Act of 1916. The act called for a system of highways that eventually would replace the railroad as the major means of surface transportation in this country.

|

As a result of this legislation, the Chicago Road became a part of the Federal Highway System as US-112, and paving began in the early 1920s. A new era had begun. Individual states organized Departments of Transportation and began a project of paving and building that in the following twenty years fostered more change than the entire preceding one hundred years. Bridge building was among the major projects undertaken during this time. The State of Michigan took a leading role developing standardized plans used for bridges throughout the state. One such plan was for the camelback, which was constructed only in Michigan and in Ontario, Canada. Several of these bridges spanned rivers along the Chicago Road. One particularly impressive bridge, circa 1922, still crosses the St. Joseph River in Mottville.

Tourism-based Travel Influences

|

The automobile had brought a new use to the highway. The road no longer served only as a means to transport goods and to carry passengers to a destination; it had become entertainment. Americans took to the road with enthusiasm. Industrialization and the resultant growth of labor unions, gave Americans the "weekend", paid vacations, leisure time, and income for travel. For the auto-tourist the corridor, which a century earlier had brought great-grandparents to a new home, now became a source of adventure. As early as the 1920s attractions intended for tourists began to appear along the highway imposing themselves on the landscape.